Gehan Gunatilleke

Introduction

Information is fundamental to the functioning of a modern democracy and is a key element of the “overall global trend towards more open government.”[1] Without information, the scope for the people to exercise power through their elected representatives becomes obviously limited. The ‘right to information’ (RTI) accordingly emerges from the idea that popular sovereignty requires a system of governance that is transparent. Sri Lanka’s Constitution of 1978 unambiguously embraces this notion of sovereignty. Article 3 states “sovereignty is in the people and is inalienable. Sovereignty includes the powers of government, fundamental rights and the franchise.” Yet Sri Lanka’s constitutional experience suggests that the articulation of popular sovereignty in the text of the constitution remains distinct from the fulfilment of this idea in practice. Transparency has scarcely featured in governance, rights jurisprudence, or elections in Sri Lanka. On the contrary, institutions have been designed to deny people information, thereby fostering a culture of secrecy as opposed to transparency.

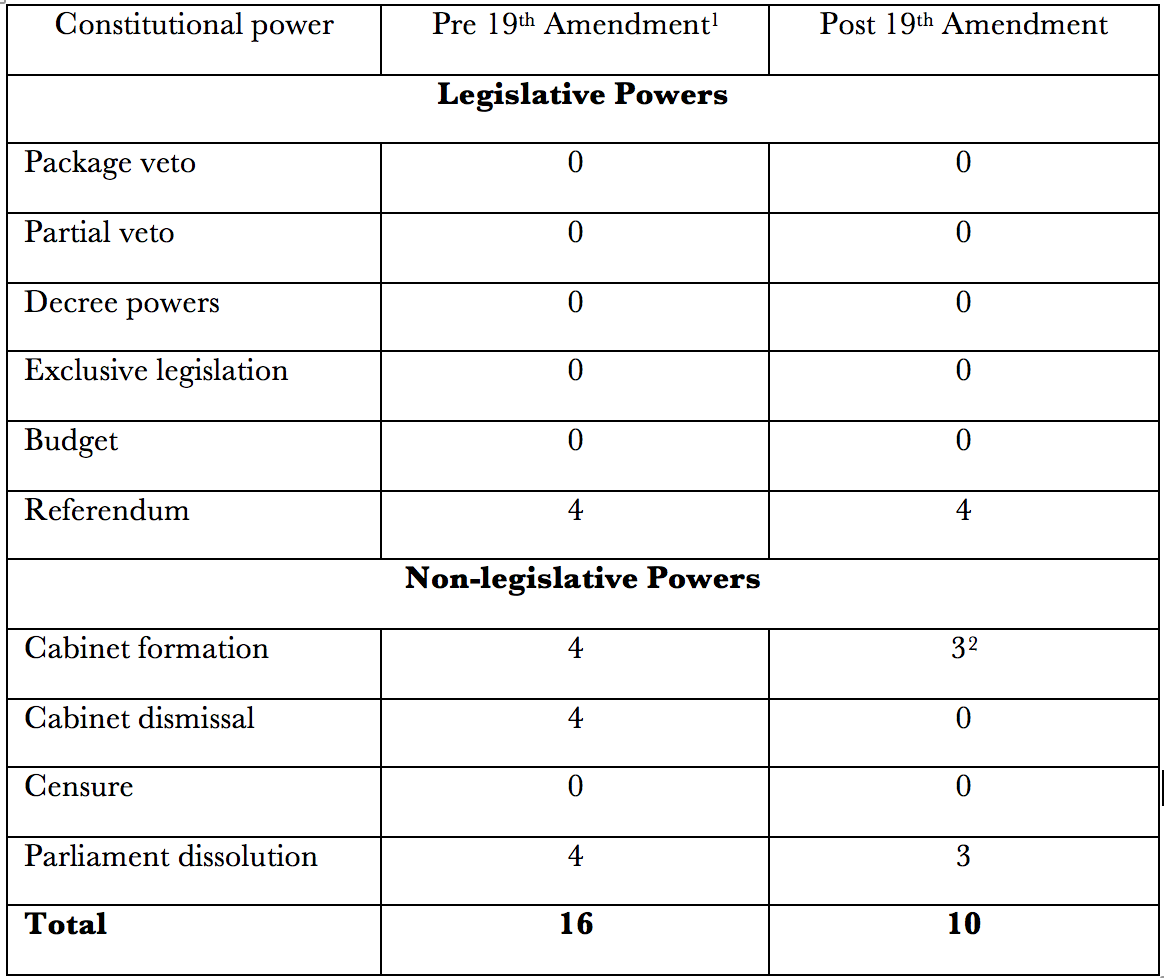

On 15th May 2015, Parliament enacted the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The amendment aimed to restore terms limits on the presidency, restrict – to some extent – the powers of the executive president, and restore institutional independence.[2] Alongside these primary aims, the amendment introduced a new fundamental right on RTI. The introduction of this right was largely welcomed as a step in the right direction, particularly in terms of expanding the gamut of justiciable rights. Yet the value of this expanded framework will ultimately be measured by the fruits of its practical application.

This chapter examines the constitutionalisation of RTI through the Nineteenth Amendment, and discusses its implications with respect to restoring the sovereignty of the people. The chapter is presented in three parts. The first part briefly discusses the philosophy behind RTI and the broad context within which the amendment was enacted. The second analyses the relevant text of the amendment and examines the extent to which RTI is guaranteed under the constitution. The final section discusses the need for further reform with an aim to build on the amendment and elaborate upon this newly recognised fundamental right.

1 Philosophy and Context

Terminology

RTI is often used interchangeably with the terms ‘freedom of information’ (FOI). There is, however, an important distinction in the terminology.[3] ‘FOI’ essentially contemplates a ‘negative’ right. The terminology implies the right of individuals to access information and the duty of the state not to impede such access except under specific, carefully defined circumstances. In this context, the state’s obligations are framed in passive terms – similar to the framing of the state’s obligations with respect to key civil and political rights, such as the freedom from torture, the freedom of speech and expression, and the freedom of association. A classic expression of FOI would be guarantees against censoring the media. It is argued that the people must be afforded the freedom of accessing information disseminated through the media, and that the state must refrain from unduly censoring or restricting such access.

The language of ‘RTI’, by contrast, implies that individuals have a right to receive information, and that the state has a corresponding duty to provide information. The terminology is similar to the ‘positive’ articulation of many socioeconomic rights such as the rights to health, education, and housing.[4] Thus, under RTI, the state’s obligations are framed in active terms; the state is expected to fulfil the right by providing information and actively facilitating access. In India, the semantics of ‘RTI’ have been preferred to ‘FOI’ precisely for this reason.[5] Similarly, in Mexico, the constitution was amended in 1977 to provide that “access to information will be guaranteed by the State” (emphasis added).[6] This conception of the right permits a broader definition of information – not only as an important ingredient for public accountability, but also as a commodity over which the people have proprietary interests. The people elect public officials to represent their interests in matters of governance and public policy, and to run the affairs of state on their behalf. Since the people confer this authority on elected representatives and public officials, the information they deal with remain the property of the people. Therefore, information is not merely of instrumental value. It is seen as ‘belonging’ to the people. As rightful owners of the information held by the state, the people have a right to access such information. Therefore, despite the significant conceptual overlap between RTI and FOI, the two articulations of the right have distinct foundations.[7]

In Sri Lanka, the terminology used has largely depended on the context of the conversation. Early conversations on the subject framed the right as a negative right. For instance, in 1996, the Committee to Advise on the Reform of Laws Affecting Media Freedom and Freedom of Expression[8] recommended the enactment of a ‘Freedom of Information Law’. The several drafts that were produced and discussed during the late 1990s and early 2000s used the terminology of ‘FOI’. In late 2014, the terminology was clearly framed in positive terms, where Maithripala Sirisena, the Common Opposition candidate for the presidential election, pledged to ‘introduce a Right [to] Information Act’.[9] This terminology was retained in the draft RTI Bill that was circulated in early 2015.[10] The Nineteenth Amendment adopts a slightly more conservative terminology, though perhaps retaining the flavour of ‘RTI’ as opposed to ‘FOI’.

The Campaign

By the time the Nineteenth Amendment was enacted in May 2015, several FOI/RTI campaigns had been launched by civil society and media actors in Sri Lanka. These campaigns warrant brief discussion in order to place the amendment in its proper context.

Between 1995 and 2000, there were several attempts to introduce constitutional reform, which included references to FOI. The Draft Constitution Bill of 2000 very specifically recognised FOI. Article 16(1) provided: “Every person shall be entitled to…the freedom to seek, receive and impart information…” (emphasis added).[11] This framing very much echoed the language of Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[12] However, due to the subsequent breakdown in talks between the two main political parties, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party and the United National Party, the Draft Constitution Bill failed upon its introduction in Parliament.

During the Chandrika Kumaratunga-Ranil Wickremesinghe cohabitation government of 2001-2004, civil society groups and media organisations succeeded in negotiating a draft FOI law.[13] This draft was an improvement on a previous Law Commission draft. It included whistle-blower protection and established an Information Commission, although it still fell short of international best practices.[14] A final version of Bill was then prepared by the Legal Draftsman’s Department and was approved by Cabinet in January 2004. However, the collapse of the government and the dissolution of Parliament in 2004 brought an abrupt end to the campaign. The draft Bill was not presented in Parliament as a result.

Following the election of current President Maithripala Sirisena in January 2015, a new campaign to enact an RTI law was launched. The new government appointed a drafting committee comprising government officials and civil society actors and produced a revised version of the 2004 Bill. The Bill was welcomed by most, but was also criticised for including broad restrictions.[15] For instance, the Bill provided that information requests shall be refused if “the disclosure of such information would…harm the commercial interests of any person” – a restriction that was patently overreaching.[16] The new Bill, however, was not tabled in Parliament prior to its dissolution in late June 2015.

It is clear that the RTI campaign in Sri Lanka has had a reasonably long history. Thus the inclusion of the right in the Nineteenth Amendment was welcomed. In this context, the amendment may be considered the first tangible legislative victory for a campaign that had hitherto endured numerous disappointments.

Jurisprudence

Prior to delving into the text of the Nineteenth Amendment, it may be useful to briefly discuss the fundamental rights jurisprudence relevant to RTI. The case law suggests that the Sri Lankan constitution implicitly recognises RTI. Two provisions in the fundamental rights chapter of the constitution are relevant in this regard. Article 10 guarantees to every person – including non-citizens – the freedom of thought, conscience and religion, including the freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice. It is possible to argue that unimpeded access to information is implicit in the freedom of thought. Thus every person within the territory of Sri Lanka has an implicit right to the information necessary for the full exercise of other freedoms such as the freedom of thought.

It is appreciated that the argument that all persons have an implicit right to information by virtue of their absolute freedom of thought can appear tenuous. However, there is judicial precedent to suggest that the argument has some merit. In Fernando v. the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (1996) Justice Mark Fernando observed – albeit obiter – that “information is the staple food of thought, and that the right to information … is a corollary of the freedom of thought guaranteed by Article 10.”[17] He added that under the constitution, “no restrictions are permitted in relation to freedom of thought,”[18] thereby implying that a broad unrestricted conception of RTI was conceivable under the constitution. Unfortunately, the case before the Supreme Court was not specifically under Article 10, and no further pronouncement was possible.

Meanwhile, there is ample jurisprudence which confirms that Article 14(1)(a) of the constitution implicitly guarantees FOI – and to an extent RTI – to Sri Lankan citizens. Article 14(1)(a) guarantees the freedom of speech and expression including publication. It is noted that, unlike Article 10, the rights under Article 14(1)(a) are subject to limitations. These restrictions must be defined by law and must be related to or in the interest of racial and religious harmony, parliamentary privilege, contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence, or national security.[19] Nevertheless, the courts have been willing to recognise that the express guarantees under Article 14(1)(a) require implied guarantees pertaining to FOI/RTI.

Early cases adopted a more cautious view of implied guarantees under Article 14(1)(a). In Visuvalingam v. Liyanage (1984), the Supreme Court observed:

“Public discussion is not a one-sided affair. Public discussion needs for its full realisation the recognition, respect and advancement, by all organs of government, of the right of the person who is the recipient of information as well. Otherwise, the freedom of speech and expression will lose much of its value.”[20]

The Court in this case advanced the notion of a negative right, as it recognised the legal standing of newspaper readers to challenge the state’s decision to ban a newspaper called The Saturday Review. Thus the Court was willing to conceive of FOI insofar as the state had a duty not to unduly restrict information. The Court held that the constitution implicitly contained FOI vis-à-vis Article 14(1)(a), although it eventually dismissed the application on its merits.

In the aforementioned case of Fernando v. the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, the Supreme Court further substantiated the relationship between express and implied guarantees of fundamental rights in the constitution. It held that express guarantees extended to and included implied guarantees necessary to make the express guarantees meaningful.[21] Hence it was held that elements relating to FOI, such as the “right to obtain and record information,” were implied guarantees that made the express guarantee of the freedom of speech and expression meaningful.[22] The Court, however, stopped short of recognising RTI simpliciter as part of the freedom of speech and expression.[23] Thus the judgement is not sufficient to advance the view that Sri Lankan citizens – by virtue of their freedom of speech and expression – also have RTI, which the state is constitutionally bound to fulfil.

In the later case of Environmental Foundation Limited v. Urban Development Authority (2005),[24] also known as the Galle Face Green Case, the Court expanded the scope of the implied right. The case involved the Urban Development Authority’s (UDA) decision to alienate state-owned property to a private company without the knowledge of the public. The Court held that, although there is no explicit reference to RTI in the constitution, the freedom of speech and expression including publication guaranteed by the constitution under Article 14(1)(a) includes the right to receive information on matters of public interest. In his seminal judgment, Chief Justice Sarath N. Silva observed:

“[T]he ‘freedom of speech and expression including publication’ guaranteed by Article 14(1)(a) to be meaningful and effective should carry within its scope an implicit right of a person to secure relevant information from a public authority in respect of a matter that should be in the public domain. It should necessarily be so where the public interest in the matter outweigh[s] the confidentiality that attach to affairs of State and official communication.”[25]

Crucially, the Court was inclined to draw a nexus between the implicit right to secure relevant information and Article 4(d) of the constitution, which articulates “the manner in which the sovereignty of the People shall be exercised in relation to fundamental rights.”[26] The Court, for the first time, acknowledged the nexus between popular sovereignty and RTI, and the necessary obligation of the state to fulfil this right. It held:

“The UDA is an organ of Government and is required by the provisions of Article 4(d) to secure and advance the fundamental rights that are guaranteed by the Constitution. It has an obligation under the Constitution to ensure that a person could effectively exercise the freedom of speech, expression and publication in respect of a matter that should be in the public domain. Therefore a bare denial of access to official information … amounts to an infringement of the Petitioner’s fundamental rights as guaranteed by Article 14(1)(a) of the Constitution.”[27]

Therefore, the Supreme Court recognised RTI simpliciter, to the extent that the information sought was in the public interest. The corresponding obligation of the state was therefore acknowledged as ‘positive’ in that it contemplated a duty to provide the relevant information to the public. The Galle Face Green Case accordingly marks an important departure from the conservative approach previously adopted by the courts. In fact the judgment set the stage for the constitutional recognition of RTI and the process through which RTI could be fulfilled. However, this opportunity was not seized, as the then government under President Mahinda Rajapaksa was instead more interested in plunging the country into a deep and pervasive culture of secrecy.[28] It was not until January 2015 that the campaign for RTI was reignited and the prospects of constitutional and statutory reform became once again plausible.

Article 14A

The Nineteenth Amendment introduced Article 14A into the fundamental rights chapter of the Sri Lankan constitution, which provides:

“(1) Every citizen shall have the right of access to any information as provided for by law, being information that is required for the exercise or protection of a citizen’s right held by:-

(a) the State, a Ministry or any Government Department or any statutory body established or created by or under any law;

(b) any Ministry of a Minster of the Board of Ministers of a Province or any Department or any statutory body established or created by a statute of a Provincial Council;

(c) any local authority; and

(d) any other person, who is in possession of such information relating to any institution referred to in sub-paragraphs (a) (b) or (c) of this paragraph.”

At the outset, it should be noted that the right envisaged by Article 14A only extends to Sri Lankan citizens. Thus its reach is narrower that that of Articles 10, 11, 12 and 13, which apply to ‘persons.’

A textual reading of Article 14A suggests that it contains three limbs. The first limb suggests that access to information under Article 14A is contingent on a pre-existing process already provided for by law. It may be reasonably assumed that the drafters of the Nineteenth Amendment contemplated a corresponding RTI law that would substantiate the fundamental right and establish a process through which citizens could access information. It was, after all, drafted at a time when an RTI Bill was also in the legislative pipeline. However, as discussed in the preceding section, the RTI Bill was not tabled in Parliament. In the absence of such supporting legislation, this limb – in isolation – is somewhat problematic, as it makes access to information dependent on a pre-existing legislative framework. It may be argued – though from a distinctly textualist standpoint – that the absence of a pre-existing legislative process through which information could be obtained precludes, in itself, such access. For example, the information sought in the Galle Face Green Case could not have been obtained from the UDA, as the UDA Law No. 41 of 1978 does not explicitly provide for the publication of agreements between the Authority and third parties. A citizen could, however, invoke the new Article 14A to obtain a copy of a draft development plan, which under Section 8G of the Law must be made available for public inspection. It is worth noting that a pre-existing statutory duty to provide information can in any event be canvassed through the administrative law remedies available under Article 140 of the constitution.[29] Hence Article 14A only appears to expand the scope of remedies available to a citizen, rather than create a completely new avenue through which RTI could be vindicated.

A more purposive reading of Article 14A suggests that a citizen could invoke the fundamental rights jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to exploit pre-existing legislative frameworks that were hitherto extremely restrictive. One example that springs to mind is the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law No.1 of 1975 (as amended by Act No.74 of 1988), which provides a limited opportunity to a person to access a public official’s assets declaration.[30] Section 5(3) of the Law provides:

“Any person shall on payment of a prescribed fee to the appropriate authority have the right to call for and refer to any declaration of assets and liabilities and on payment of a further fee to be prescribed shall have the right to obtain that declaration.”

However, Section 8(1) of the Law imposes a peculiar restriction on any person who obtains information through the process defined under the Law. It provides:

“A person shall preserve and aid in preserving secrecy with regard to all matters relating to the affairs of any person to whom this Law applies, or which may come to his knowledge in the performance of his duties under this Law or in the exercise of his right under subsection (3) of section 5 (emphasis added).”

Thus the Law prevents the disclosure of an assets declaration obtained by virtue of Section 5(3). A person only appears to have a right to obtain the information, and not to share with others or publish such information, even in the public interest. On obtaining the assets declaration, a person can only refer the declaration to the appropriate authority, which could then conduct an investigation or take further action.

With the introduction of Article 14A, it is possible to argue that a citizen[31] has a right to invoke the fundamental rights jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to gain access to the assets declarations of certain public officials. The pre-existing process provided for by law, i.e. the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law, arguably qualifies an assets declaration to be included under Article 14A, provided it satisfies limbs two and three discussed below. In this context, it is worthwhile considering whether a citizen could invoke the fundamental rights jurisdiction of the Court without first seeking to obtain the asset declaration via Section 5(3) of the Law. Such an interpretation will certainly require a creative departure from the literal meaning of Article 14A. However, if such an interpretation was upheld, a citizen may no longer be bound by the restrictions of Section 8(1) of the Law, as he did not obtain the declaration by exercising his right under Section 5(3) of the Law in the first place. The citizen may therefore share or publish the assets declaration obtained through a fundamental rights application. This interpretation, though clearly optimistic, clashes neither with Article 14A(2) nor Article 16(1) of the constitution.[32] Article 14A(2) provides:

“No restrictions shall be placed on the right declared and recognized by this Article, other than such restrictions prescribed by law as are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals and of the reputation or the rights of others, privacy, prevention of contempt of court, protection of parliamentary privilege, for preventing the disclosure of information communicated in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.”

It could be argued that in the absence of any direct reliance on the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law, an assets declaration does not fall within any of the restrictions prescribed by law. The secrecy provisions of the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law do not directly refer to any of the prescribed grounds listed in Article 14A. They do, however, by their very definition, qualify as “information communicated in confidence.” Yet if the asset declaration is obtained through the intervention of the Court and not through Article 5(3), it becomes difficult to maintain that the communication was confidential. Thus a petitioner could potentially argue that the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law does not restrict the right to access a public official’s asset declaration through a fundamental rights application.

The second limb of Article 14A stipulates that the relevant information is required for the “exercise or protection of a citizen’s right.” It is reasonable to assume that the terms ‘citizen’s right’ relates to the fundamental rights recognised in the constitution. The term ‘right’ is not used in any other context. Thus, for example, a citizen has a right to access a particular piece of information if such information relates to his or her freedom of speech and expression including publication guaranteed by Article 14(1)(a). Similarly, under Article 14A, a citizen could seek to access information required to protect his or her right to equality guaranteed by Article 12(1).

This limb, however, restricts the scope of the right, as it attaches another prerequisite to the exercise of right. For instance, the right to housing is not explicitly recognised under the Sri Lankan constitution. Therefore, a citizen may not ex facie be eligible to access information held by the Ministry of Housing. The citizen concerned will need to establish that the information sought relates to his or her right to equality or some other justiciable right found in the fundamental rights chapter of the constitution in order to invoke the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. In this context, Article 14A mainly succeeds in making express what the Supreme Court has previously held to be implied. RTI was considered to be an implied right only because it related to Articles 10 and 14(1)(a). By restricting the scope of its application to instances where another right is involved, Article 14A entrenches the principle enunciated by the Supreme Court. To its credit, however, Article 14A expands on the implied right previously recognised by the Court. As one might recall, the Court in the Galle Face Green Case opined that the implied right only extends to information required for the exercise of rights under Article 14(1)(a) in the public interest. Article 14A appears to dispense with the public interest prerequisite and also includes information that is only relevant to the exercise or protection of an individual citizen’s rights.

In the case of assets declarations, it could be argued that information on the assets of a government department head, or a chairperson of a public corporation is relevant to the exercise of a citizen’s freedom of speech and expression including publication. If, for example, a journalist required such information for an article, such information could potentially be sought through a fundamental rights application naming the Secretary to the relevant Ministry as a respondent.[33]

The third and final limb of Article 14A concerns the actor or institution in possession of the information. Article 14A(1) requires that the relevant information be in the possession of certain specified institutions, or ‘any other person’ in possession of information relating to a specified institution. Article 14A(1)(a), however, makes an explicit reference to the ‘state.’ The ‘state’ is not specifically defined in the Sri Lankan constitution. Therefore, such reference must be interpreted to mean ‘agents’ of the state, including all state functionaries and officials.[34] It remains to be seen whether the definition of ‘state’ would be limited to officials exercising executive and administrative action. Regardless of the precise definition of the term, Article 17 provides that a fundamental rights application would lie only if the infringement of Article 14A was by ‘executive or administrative action.’[35] Thus relief could be sought against a private actor in possession of relevant information provided the actor falls within the scope of ‘executive or administrative action.’ It is noted that the jurisprudence of the Court has extended the scope of ‘executive or administrative action’ to include private entities that act as agents of the state.[36] However, Article 14A casts a much wider net, as it applies to anyone in possession of certain types of information. In this context, it would be interesting to discover the Court’s approach to reconciling what appears to be an incongruence between Article 14A and Article 17.

Once again, in the case of assets declarations, the relevant information is bound to be in the possession of a state functionary or official, thereby falling within the ambit of Article 14A. For example, in the case of assets declarations of office-bearers of recognised political parties, the relevant information would be in the possession of the Commissioner of Elections.[37] Thus a citizen could potentially file a fundamental rights application to compel the Commissioner to release an assets declaration, which the citizen argues is required for the exercise or protection of another fundamental right.

Weaknesses in the New Framework

The aforementioned limbs of Article 14A are extremely restrictive. In the absence of existing laws that provide for access, Article 14A would be virtually inapplicable. Even where laws exist – such as the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law – a creative interpretation of Article 14A would ultimately be necessary for it to be useful in vindicating RTI. Thus, from a rights perspective, Article 14A appears to be a disappointment. Three key weaknesses in Article 14A may be highlighted.

First, it is worth noting that the original version of Article 14A as per the draft Nineteenth Amendment Bill was far better than the final version that was enacted. Only one of the three aforementioned restrictive limbs was included in the version that was first tabled in Parliament.[38] The original version only included the prerequisite that the relevant information be required for the exercise or protection of a citizen’s right. Yet the original version made no reference to a prerequisite that access must be “as provided for by law.” A citizen would not have been required to first establish that the access he or she sought was already provided for by existing legislation. Thus, in the absence of supporting RTI legislation, Article 14A’s potency appears to be limited. Moreover, the original version did not restrict the terms “any other person” to those who had in their possession information related to a specified institution. Instead, a citizen could seek access to any information held by any person, provided that the information was required for the exercise or protection of a citizen’s rights.

Second, the final version of Article 14A included more restrictions on the right. The original version of the Article did not include the prevention of contempt of court and the protection of parliamentary privilege. Therefore, amending provisions to existing laws (or new laws) that specifically restrict RTI on the basis of preventing the contempt of court and protecting parliamentary privilege may be enacted in the future. In the context of the freedom of speech and expression, both these grounds for restriction have been viewed with deep suspicion. For instance, the Law Commission of Sri Lanka observed that “[t]oo harsh a law on contempt can act as a barrier to the development of a healthy and vibrant jurisprudence.”[39] Similarly, the R.K.W. Goonesekere Committee concluded that constitutional provisions that made parliamentary privilege a ground for restricting free speech were “wholly inconsistent with Sri Lanka’s obligations under international law.”[40] It is no doubt reasonable to extend these apprehensions to RTI.

Finally, Article 14A is arguably impracticable, as it places a heavy burden on the Supreme Court to monitor compliance with its orders granting access to information. The Court would not be unaccustomed to its ‘just and equitable’ jurisdiction under Article 126(4) of the constitution. Such a jurisdiction often requires regular compliance monitoring. Yet the Court is still likely to be severely inconvenienced by the prospect of directing respondents to grant access to information and thereafter dealing with complaints on non-compliance. Questions of compliance may be better left to a dedicated body such as an Information Commission with a specific mandate to hear complaints regarding the denial of information requests. The Nineteenth Amendment does not establish such a body, nor does it name such a body as one of the institutions falling within the purview of the re-established Constitutional Council.[41] The Council was specifically re-established under the Nineteenth Amendment to depoliticise public institutions and restore institutional independence. Therefore, even if an Information Commission is later established through appropriate legislation, there are no constitutional guarantees pertaining to its independence.

Conclusion: The Challenge Ahead

The foregoing analysis reveals that the Nineteenth Amendment fails to meaningfully constitutionalise RTI. Three concluding observations may be offered in this respect. These observations may also be useful in terms of setting the agenda for future reform.

First, it is crucial that the Sri Lankan state and citizenry view RTI as a multifaceted right. It is important that the right is viewed both as a negative right and as a positive right. Individuals must be guaranteed both the right to freely access information and the right to easily receive information. In this context, the state has corresponding duties not to unduly restrict access to information and to provide information to individuals. Establishing a culture of transparency will therefore require a conceptualisation of RTI that is holistic; and a holistic conception of the right will need to be reflected in the text of the constitution. In this context, the relevant provisions in the fundamental rights chapter ought to frame the right in the broadest sense possible, with minimal prerequisites and restrictions. For instance, the restrictive language analysed in the preceding discussion would need to be removed from the current text of Article 14A. Additionally, it may be necessary to explicitly recognise the negative aspect of RTI by expanding the scope of Article 14(1)(a). The current language pertaining to the freedom of speech and expression could be expanded to include a right to ‘seek, receive and impart information’ in line with Article 19 of the ICCPR. If these reforms are treated as high on the constitutional reform agenda, and are introduced in the short to mid term, it is possible to conceive of a deeper constitutionalisation of the right.

Second, the constitutionalisation of RTI must be supplemented by legislation that elaborates upon the fundamental right. The current RTI Bill is worth noting in this context. The Bill sets out a reasonably sound process through which a citizen could apply for and access information in the possession of a public authority. The term ‘public authority’ includes private entities or organisations “carrying out a statutory or public function or a statutory or public service … but only to the extent of activities covered by that statutory or public function or that statutory or public service.”[42] Moreover, the Bill contains a prevalence clause. Section 4(1) of the Bill provides:

“The provisions of this Act shall have effect notwithstanding anything to the contrary in any other written law, and accordingly in the event of any inconsistency or conflict between the provisions of this Act and such other written law, the provisions of this Act shall prevail.”

This clause is encouraging, as it sets out the basis on which the future RTI Act could supersede older laws that are designed to restrict access to information. The Act would effectively trump laws such as the Official Secrets Act No.32 of 1955, which exerts considerable pressure on officials to withhold information that may be considered sensitive, and the Sri Lanka Press Council Law No.5 of 1973, which restricts the publication of information that may “adversely affect the economy.”[43] The prevalence clause may also empower public servants constrained by non-disclosure provisions in the Establishments Code.[44]

Third, a process of conscientisation[45] ought to take place to ensure that the people understand the nature and extent of their RTI and acknowledge its inherent relationship to their sovereignty. Constitutional and statutory reform must be followed by a long-term strategy that aims to create a RTI consciousness among the people. The experience in India suggests that such a process may take years, particularly as individuals become more accustomed to the RTI processes in place and begin to understand their use. Moreover, the culture of secrecy entrenched within state institutions will take years to unravel. It will no doubt take several years of trial and error and institutional learning before the state begins to effectively fulfil RTI. In this context, legal reform will by no means be a sufficient indication of progress.

It would appear that the new Sri Lankan government that was installed after the general elections of August 2015 is confronted with a threefold challenge. It must first expand on the constitutional articulation of the right in order to ensure that the constitutionalisation of RTI is meaningful. Moreover, it must meet the public’s expectations of an effective statutory framework that elaborates on the right by enacting an RTI Act sooner rather than later. Finally, it must embark on a programme of action that transforms the culture of secrecy that presently plagues state institutions and actors. It is only through such a holistic approach to RTI that the people’s sovereignty – that constitutional first principle – might find meaningful expression in Sri Lanka.

[1] See T. Mendel (2014) Right to Information: The Recent Spread of RTI Legislation (Washington: World Bank): p.1.

[2] See A. Welikala, ‘The Nineteenth Amendment is a constitutional milestone in Sri Lanka’s ongoing political development’, The UCL Constitution Unit Blog, May 2015: http://constitution-unit.com/2015/05/21/the-nineteenth-amendment-is-a-constitutional-milestone-in-sri-lankas-ongoing-political-development (last accessed 12th March 2016); G. Gunatilleke & N. de Mel (2015) 19th Amendment: The Wins, the Losses and the In-betweens (Colombo: Verité Research) for discussions on the contents of the amendment.

[3] Mendel (2014): p.1. The author notes: “Originally often referred to as freedom of information laws (Australia, Norway, United States) and access to information or documents laws (Canada, Colombia, Denmark), a more recent trend (starting with India in 2005) had been to use the title RTI laws, reflecting the recognition of RTI as human right.”

[4] For a useful discussion on positive and negative rights in constitutional law, see D.P. Currie, ‘Positive and Negative Constitutional Rights’ (1986) The University of Chicago Law Review 53(3): pp.864-890. For a broader discussion, see J. Donnelly (2003) Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press): p.30.

[5] See the Right to Information Act 2005 (India). The long title of the Act describes it as “An Act to provide for the setting out of the practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, the constitution of a Central Information Commission and State Information Commissions and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.” Also see R. Jenkins & A.M. Goetz, ‘Accounts and Accountability: Theoretical Implications of the Right-to-Information Movement in India’ (1999) Third World Quarterly 20(3): pp.603-622.

[6] Constitution of Mexico (1917): Article 6, as amended.

[7] For a further discussion on comparative experiences, see J.M. Ackerman & I.E. Sandoval-Ballesteros, ‘The Global Explosion of Freedom of Information Laws’ (2006) Administrative Law Review 58(1): pp.85-130.

[8] R.K.W. Goonesekere Committee Report (1996) Report of the Committee to Advise on the Reform of Laws Affecting Media Freedom and Freedom of Expression; also see K. Pinto-Jayawardena & G. Gunatilleke, ‘One Step Forward, Many Steps Back: Media Law Reform Examined’ in W. Crawly, D. Page & K. Pinto-Jayawardena (Eds.) (2015) Embattled Media: Democracy, Governance and Reform in Sri Lanka (London: Institute of Commonwealth Studies): p.188.

[9] Manifesto of the New Democratic Front (2014): p.17.

[10] The long title of the draft Right to Information Bill (L.D.O 4/2015) describes it as “An Act to provide for the right to information; specify grounds on which access may be denied; the establishment of the Right to Information Commission; the appointment of Information Officers; setting out the procedure for obtaining information and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.”

[11] Bill (No.372) to repeal and replace the Constitution of the Democratic Social Republic of Sri Lanka (August 2000): Article 16(1).

[12] Article 19(2) of the ICCPR provides: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.” See UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16th December 1966, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 999, p.171.

[13] Pinto-Jayawardena & Gunatilleke (2015): p.207.

[14] See G. Gunatilleke (2014) The Right to Information: A Guide for Advocates (Colombo: Sri Lanka Press Institute; UNESCO): p.61, for an analysis of both drafts.

[15] See Verité Research (2015) Observations on the Draft Right to Information Bill.

[16] Right to Information Bill (L.D.O. 4/2015): Section 5(1)(d).

[17] (1996) 1 SLR 157: p.171.

[18] Ibid: p.179.

[19] See Constitution of Sri Lanka (1978): Article 15(7), which provides: “The exercise and operation of all the fundamental rights declared and recognized by Articles 12, 13(1), 13(2) and 14 shall be subject to such restrictions as may be prescribed by law in the interests of national security, public order and the protection of public health or morality, or for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others, or of meeting the just requirements of the general welfare of a democratic society. For the purposes of this paragraph “law” includes regulations made under the law for the time being relating to public security.”

[20] (1984) 2 SLR 123: p.131.

[21] (1996) 1 SLR 157: p.179.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] SC (F.R.) Application No. 47/2004, judgment dated 28th November 2005.

[25] Ibid: p.6.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid: p.7.

[28] See Pinto-Jayawardena & Gunatilleke (2015).

[29] Article 140 of the constitution provides: “Subject to the provisions of the Constitution, the Court of Appeal shall have full power and authority to inspect and examine the records of any Court of First Instance or tribunal or other institution, and grant and issue, according to law, orders in the nature of writs of certiorari, prohibition, procedendo, mandamus and quo warranto against the judge of any Court of First Instance or tribunal or other institution or any other person.”

[30] According to Section 2 of the Law, the relevant officials include Members of Parliament, Judges, Public Officers appointed by President or Cabinet Ministers, staff officers in Ministries and government departments (i.e. additional secretaries, deputy secretaries, assistant secretaries and heads of departments), chairmen, directors, board members, staff officers of public corporations, elected members and staff officers of local authorities, office bearers of ‘recognised’ political parties, and executives of trade unions.

[31] Article 14A(3) provides: “In this Article, “citizen” includes a body whether incorporated or unincorporated, if not less than three-fourths of the members of such body are citizens.”

[32] Article 16(1) provides: “All existing written law and unwritten law shall be valid and operative notwithstanding any inconsistency with the preceding provisions of this Chapter.” It is noted that the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law No.1 of 1975 (as amended) continues to be valid and operative. Article 14A will (if at all) only provide for an alternative channel through which a citizen could obtain an asset declaration of a public official.

[33] See Section 4(d) of the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law No.1 of 1975 (as amended).

[34] See Wickremratne v. Jayaratne (2001) 3 SLR 161: p.176. The Court of Appeal observed that the “State … has necessarily to act through its officials or functionaries”. Also see Peter Leo Fernando v. The Attorney General (1985) 2 SLR 341.

[35] Article 17 of the Constitution of Sri Lanka (1978) provides: “Every person shall be entitled to apply to the Supreme Court, as provided by Article 126, in respect of the infringement or imminent infringement, by executive or administrative action, of a fundamental right to which I such person is entitled under the provisions of this Chapter.”

[36] See Leo Samson v. Sri Lankan Airlines (2001) 1 SLR 94; Jayakody v. Sri Lanka Insurance and Robinson Hotel (2001) 1 SLR 365.

[37] Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law, No.1 of 1975 (as amended): Section 4(Ia).

[38] See Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution (L.D.O. 20/2015): Section 2.

[39] The Law Commission of Sri Lanka, Draft Contempt of Court Bill proposed by the Law Commission of Sri Lanka (2008), http://lawcom.gov.lk/web/images/stories/reports/draft_contempt_of_court_bill_2008.pdf (last accessed 13th March 2016): p.5.

[40] Pinto-Jayawardena & Gunatilleke (2015): p.204. Also see R.W.K. Goonesekere Committee Report (1996): pp.13-14.

[41] Article 41B(1) provides: “No person shall be appointed by the President as the Chairman or a member of any of the Commissions specified in the Schedule to this Article, except on a recommendation of the Council.” The Schedule comprises: (a) The Election Commission (b) The Public Service Commission (c) The National Police Commission (d) The Audit Service Commission (e) The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (f) The Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (g) The Finance Commission (h) The Delimitation Commission and (i) The National Procurement Commission.

[42] Right to Information Bill (L.D.O. 4/2015): Section 46.

[43] See Sri Lanka Press Council Law No.5 of 1973: Section 16(4). Other laws that restrict access to particular types of information include the Profane Publication Act No.41 of 1958, the Public Performance Ordinance No.7 of 1912, the Obscene Publications Ordinance No.4 of 1927, and the Prevention of Terrorism Act No.48 of 1979.

[44] See Establishments Code of Sri Lanka: Section 3 of Chapter XXX1 of Volume 1 and Section 6 of Chapter XLVII of Volume 2. The Code provides: “No information even when confined to statement of fact should be given where its publication may embarrass the government, as a whole or any government department, or officer. In cases of doubt the Minister concerned should be consulted.”

[45] “Conscientisation” is a concept developed by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. It is usually defined as “[t]he process of developing a critical awareness of one’s social reality through reflection and action.” See “Concepts used by Paulo Freire”, http://www.freire.org/component/easytagcloud/118-module/conscientization/ (last accessed 12th March 2016). Also see P. Freire (2000) Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition (New York: Continuum).