Laksiri Fernando

Introduction

In recent debates on Sri Lanka’s future and required political change, academics and political analysts have extensively discussed constitutional and governance issues,[1] but not so much matters related to ‘political culture’ or ‘electoral behaviour.’ There has been some understanding for some time that the key ideology that influences the political behaviour of political leaders as well as the general public has been ‘nationalism,’ of various varieties and different types,[2] but no particular studies have been conducted to ascertain their influence on electoral behaviour in recent times.[3] Much of the prognosis on the adversarial effects of nationalism/s in the country was related to ‘linguistic nationalism’,[4] ‘ethno-nationalism’[5] or ‘separatist nationalism.’[6] On the normative side, however, except for some efforts to promote ‘civic nationalism’ in contrast to ‘ethno-nationalism’,[7] the prospects or possibilities for the emergence of more sober or grounded politico-psychological changes in the form of ‘cosmopolitanism’ has never been contemplated before.

The dramatic political changes that swept the country at the presidential elections in January, and parliamentary elections in August 2015, to re-establish democracy and good governance, however demonstrate a certain maturity of the electorate that could be interpreted as a small but a definitive move towards cosmopolitanism.[8] This was predominantly within a context of a strong parochial discourse and xenophobic movement on nationalism, called jathika chinthanaya (nationalist thought), which attempted to preserve not only the status quo after the end of the war on terrorism, but also to move beyond on a further ethno-nationalist direction.[9] After the aforesaid electoral breakthroughs in January and August, the newly formed ‘national government’ has demonstrated a programme of action with certain traits of cosmopolitanism particularly in the areas of foreign affairs and economic policy in recognition of certain global realities.

The purpose of the present chapter therefore is twofold. Considering that cosmopolitanism is a new concept in the Sri Lankan context (although with some past roots), the first part of the chapter would be devoted to elucidating the main facets of that concept relevant to Sri Lankan debates and developments. The second part thereafter is devoted to ascertain the emergence of cosmopolitan trends and tendencies, particularly at the two elections with preliminary empirical evidence based on voting patterns and electoral demography.

The Concept and Philosophy of Cosmopolitanism

Historically speaking, the concept of cosmopolitanism does not belong to one writer or school of thought. It has been used widely and diffusedly throughout centuries and only in recent times has a certain crystallisation of the concept emerged both as recognition of ‘globalisation’ and also as a rational critique of it.[10] It is undoubtedly a concept counter to ‘narrow nationalism’ in the internal dimension, which also deviates from crude globalisation on the external frontier.[11] The term, which might still not be very popular or attractive in everyday political parlance, nevertheless is useful as a model of applied theory in visualising or analysing certain political trends and recent changes.

Two Thinkers

It is customary to contrast two thinkers, one ancient and the other modern, Diogenes (404-323 BCE) and Emmanuel Kant (1724-1804), to elucidate the evolution of the concept from an individual notion to a much broader social conception. However, it should be noted that the ancient Stoics advocated a similar idea to Kant during the Greek and Roman periods, although this became somewhat tainted with Cicero’s advocacy of the ‘Empire.’ The Stoic advocacy of the notion was as a ‘cosmic community’, which transcends one’s national boundary especially in terms of justice, peace, and equality. This is the same meaning today.

Diogenes of Sinope, however, is considered the originator of the concept, or the term he used: Kosmopolites (citizens of the world). He was famous for carrying his daytime lamp as if to find the ‘honest man’ in the world. Since then cosmopolitanism has been part of moral philosophy. This Cynic philosopher, Diogenes, used to travel almost everywhere possible in the Mediterranean in his ragged clothes and when he was asked where he came from, he used to answer I am from nowhere, ‘I am a citizen of the world.’ His cosmopolitanism was thus eccentric, rootless, or represented extreme individualism, and might not be good for anyone today. This has been one criticism against cosmopolitanism even thereafter. Jean-Jacque Rousseau once said cosmopolitans argue that ‘they love everyone, in order to have the right to love no one.’[12]

The enlightened modern philosopher, Emmanuel Kant, in the late eighteenth century was different. He turned cosmopolitanism on its feet. Therefore, the modern political conception of cosmopolitanism traces its origins to Kant and not to Diogenes. Kant’s conception of a cosmopolitan is not as the rootless traveller who picks cultural titbits from different countries. It is an enlightened attitude and a ‘world outlook’ towards plurality, tolerance, multiculturalism, and co-existence. As Pauline Kleingeld explained:

“Instead, on Kant’s view, cosmopolitanism is an attitude taken up in action: an attitude of recognition, respect, openness, interest, beneficence and concern towards other human individuals, cultures and peoples as members of one global community.”[13]

Kant was not a person who had travelled much or travelled at all. He lived in his hometown Konigsberg, Germany, most of the time. With its seaport, university, government offices, and international trade, he believed that he could easily connect with different languages, religions, and cultures, broaden his knowledge and be part of a ‘common humanity.’ This does not however deny the merit of travelling for the benefit of experience, knowledge or world outlook. The point is that Kant’s cosmopolitanism was not rootles or unconcern for one’s own culture or upbringing. Even Kant believed that cosmopolitans can or ought to be ‘good patriots.’

The Kantian View

Kant developed cosmopolitanism beyond a mere moral philosophy. In that effort the concept came closer the modern political realities or political realism. It should be noted that he was not the only thinker who advocated cosmopolitanism during his time. Three facets of cosmopolitanism that Kant talked about were political, economic, and cultural. Moreover, he was the first person to develop some clear notions of international institutional arrangements within which cosmopolitanism could exist and thrive. The relevance of these ideas loom large today in the context of international obligations of countries and individuals in respect of universal human rights and international justice. Recent debates and changes in Sri Lanka could also be viewed in this light. According to this view, the fate of individuals particularly in the realm of human rights in a country is beyond the formal jurisdiction of that country and is a concern of the global community at large. The concept of ‘responsibility to protect’ (R2P), recognised by the UN, emerges from that premise.[14]

As in the case of any other philosophy, there are extremes even in the case of cosmopolitanism. The value of the Kantian conceptualisation is the avoidance of these extremes. Taking the Cynic notion of cosmopolitanism, detractors always argued about the seeming contradiction between the notion of ‘world citizen’ and the ‘citizen of a country.’ According to the Kantian view, these are two dimensions of the same citizenship, emerging from common humanity, the correlation of which would be positive given the way both national actors and the international players interact with each other. According to Kant, the ideal of correlation that could happen is not through a ‘world state’ but a voluntary federation or a league of nations. In these views, he undoubtedly presaged the formation of the League of Nations (1920) and later the United Nations (1945). Kant was a defender of the plurality of states and not the other way round.

Although there were traces of a racial theory in Kant’s early writings,[15] these racial hierarchical views became modified or abandoned later in the 1790s, and he was a firm advocate of cultural plurality in the world, colonial parts of the globe included. Kant held a theory of rights and in the same vein he defended a right to cosmopolitanism. It incorporated a ‘right to hospitality’ applied to migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, or similar groups who need assistance from other states or the international community then or today.

Kant is one who extended cosmopolitanism to embrace international trade. It is often viewed as ‘free-market cosmopolitanism’. However, even during his time, free-market cosmopolitanism fundamentally differed from free-market liberalism or today’s neo-liberalism. He brought the notion of ‘economic justice’ to the notion of free-market cosmopolitanism. It was his view that international trade promotes peace and perpetual peace. He was not advocating unbridled free trade. As Pauline Kleingeld showed,

“… Kant’s legal and political theory (especially his republicanism, his theory of property, and his defence of state-funded poverty relief) implies that trade should first of all be just, and that it can be ‘free’ trade only within the bounds of justice.”[16]

A brief look at Kant’s Perpetual Peace (1795) might be the best way to sum up his views on cosmopolitanism.[17] Although his focus was mainly on world peace, his propositions are equally valid for peace within a country like Sri Lanka. Kant was not talking about any kind of peace or temporary peace but perpetual peace. To him, no peace is everlasting unless underlying causes of war or violence are addressed. Given the human inclination for aggression and violence, he opined, perpetual peace also require strict rules and laws based on justice. In a world context, as he said, unless laws are based on addressing the issues of global citizens and their rights, no peace or stability could be achieved in a perpetual manner. World law (or cosmopolitan law) should not merely be the laws between states, but the laws of or for the global citizens. In this respect, he advocated a new vision for international law. The same goes for the laws within states, whether fundamental (constitutional) law or ordinary law. They should address the needs and aspirations of the citizens. This applies in assessing the constitutional reforms in Sri Lanka including the Nineteenth Amendment and future constitution-making.

Cosmopolitanism Studies

It is customary to consider the period since the French Revolution (1789) as the age of nationalism.[18] Kant was an exception or aberration to this period. Within this wave of strong nationalism, notions of cosmopolitanism became submerged if not completely disappeared at least until the end of the Second World War. Marxism was another philosophy which tried to counter nationalism through internationalism, but its many advocates have succumbed to nationalism through various pretexts.[19] It is only recently that academic Marxism has been in a position to influence the revival of contemporary cosmopolitanism. There were sincere attempts to prophecy the demise of nationalism after the end of the war by academics like Elie Kedourie,[20] but the attempt became submerged thereafter within the euphoria about nationalism, and much worse, ethnonationalism. But ethnonationalism was not even nationalism proper but its decomposition. It was Kedourie’s view that ‘for an academic to offer sympathy for nationalism is virtually impertinent.’ His failure or weakness perhaps was in not looking for alternatives. It is in this context that the value of increased academic interest in cosmopolitanism studies could be appreciated. These studies are not new but old as we have outlined. Therefore it is also independent from recent global studies or globalisation studies. As a normative philosophy, the value of cosmopolitan studies has enlarged nevertheless because of globalisation. As Gerard Delanty has argued, “The world may be becoming more and more globally linked by powerful global forces, but this does not make the world more cosmopolitan.”[21]Therefore, in the broadest meaning of the term, cosmopolitanism is about broadening the moral, social, cultural and political horizons of people, leaders, and organisations beyond their close confines. It also means an attitude of openness as opposed to closure within and outside a country. It is primarily about going beyond the ‘iron cage’ of nationalism, whether the country is socialist or capitalist.

There are two major reasons why the concept and philosophy of cosmopolitanism has become crucially important since the last decade of the twentieth century. First is globalisation, which has created enormous space for cosmopolitanism in whatever variety you speak of the concept. Technological integration of the world has become the infrastructure through which cosmopolitanism is and can be promoted. If cosmopolitanism is not a natural outcome of globalisation, it has become an imperative because of the threats associated with globalisation. Globalisation has even produced ideas rejecting cosmopolitanism or calling for a new form of cosmopolitanism. The call is for global citizens without states.[22] However, the main theorists of cosmopolitanism and more realist academics have held the fort. There is no rejection of the state in contemporary cosmopolitanism. Jurgen Habermas has come with ‘constitutional patriotism’ and Ulrich Beck even with ‘cosmopolitan nationalism.’ Delanty’s conception is ‘critical cosmopolitanism.’[23]

Second is the collapse of communism. Developments in this sphere have been bizarre and contradictory. Considering the nature of socialist and communist ideologies, one could have assumed that these countries were favourable to cosmopolitanism. Unfortunately, that was not the case. In the case of some Eastern European countries, some form of cosmopolitanism was applied, although selectively.[24] However, this was not the case in the Soviet Union, and even now, the countries of the former union have not been able to overcome the situation completely. Particularly during the Stalinist period and even thereafter, those who professed any form of free cosmopolitanism, except a limited form of regime sanctioned ‘international solidarity,’ were considered traitors or ‘enemies of communism.’ This is still the case in North Korea or even the much economically opened up China. Only Cuba shows clear signs of deviating from such a closed situation. Although the collapse of communism opened up space and opportunities for cosmopolitanism, the actual developments have still not taken place in many countries.

There are many other reasons why cosmopolitanism has become important today. Apart from its utility in countering narrow nationalism, cosmopolitanism has become important as a theoretical framework in understanding many social changes in our midst in Sri Lanka or overseas. As this is being written, thousands and thousands of refugees are fleeing the Syrian crisis and are arriving in Europe, crossing difficult borders seeking ‘cosmopolitan hospitality.’ Tracing social changes favourable to cosmopolitanism since the early 1990s, Delanty maintained that they are linked up with the “expansion of democracy and the extension of the space for the political.”[25] Some of the other developments that he traced were the end of Apartheid, Tiananmen Square upheavals, and democracy movements in the Arab world. There are many others with him who have also acknowledged the importance of the two hundredth anniversary of Kant’s 1795 work Perpetual Peace in 1995 as an important landmark in the revival of cosmopolitanism. Delanty also noted the following.

“The 1990s were marked not only by such major political events of global significance, but in addition by the arrival of the internet and an epochal revolution in communication technologies which led not only to the transformation of everyday life and politics but capitalism too. The sense of epochal change was enhanced with a sense of a new millennium.”[26]

It is on the basis of the above theoretical and conceptual premises, although not comprehensive by any means, that an attempt would be made in the next part of this chapter to understand the recent political changes in Sri Lanka in terms of cosmopolitanism and/or moving away from narrow nationalism.

- Understanding the Challenges of Change

The interpretation of political change at the two recent elections, in January and August 2015, is the main focus of this second part of the chapter from the point of view of cosmopolitanism that I have outlined above. The dramatic character of this change was signified by the ousting of the leader, the former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who in fact won the war against ‘separatism and terrorism’ just six years back in 2009,[27] and therefore the change could safely be interpreted as a – small nevertheless significant – move away from strong ethnonationalism towards a desirable form of cosmopolitanism. The reason or the justification to interpret the election results as a move away from strong ethnonationalism is the fact that the former President Rajapaksa contested both the presidential elections in January and the parliamentary elections in August primarily on the basis of an ethnonationalist election platform.

As far as I am aware, so far, there are no empirical studies conducted on the correlation between the emergence of cosmopolitan trends and electoral or regime change in countries where previously politics were dominated by parochial regimes and narrow nationalism. However, recently Miyase Christensen and André Jansson noted, “Iranian national elections of 2009, the Occupy Movement and the Arab Spring, taken together, have opened up a cosmopolitan space of global debates through popular communication networks.”[28] Their focus in discussing the cosmopolitan trends is in relation to the media. It is on the same vein that Lilie Chouliaraki discussed two case studies, the Haiti earthquake and the Egyptian uprising.[29] Of course the role of the new media or more particularly social media was conspicuous in electoral change, generating cosmopolitan orientations among the voters in Sri Lanka.[30] However, the present interpretation goes beyond this and analyses some important glimpses of voter behaviour and changing electoral demography in Sri Lanka in analysing electoral change and the emergence of cosmopolitan trends.

In addition to the electoral change, accompanied by majority-minority alliances, civil society activities and movements of professional groups, there have emerged certain notions, propositions, and policies that could be associated with some form cosmopolitanism. A major issue at the presidential elections in January for example was ‘good governance’ or ‘compassionate government’ (maithri palanayak). This was contrasted to the then prevailing rule, which was criticised as authoritarian, corrupt, and nepotistic. The abolition or a fundamental modification of the executive presidential system was promised and it was put into practice, whatever the weaknesses or deficiencies, through the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution under the new minority government in April 2015. A most important aspect of the Nineteenth Amendment was the reinstatement of the Constitutional Council and the independent commissions which could give a cosmopolitan orientation to the state administration and structures, drawing the best talent from all communities in society.

At the parliamentary elections in August, the leading coalition, the United National Front for Good Governance (UNFGG), declared a policy of ‘Social Market Economy’ for the first time in the country. If this is implemented properly, it would be a major boost to cosmopolitanism. Most importantly, the foreign policy orientation has shifted significantly from an anti-Western and anti-UN posture to cooperation and constructive collaboration. This has become very clear from the current government’s position at the UN Human Rights Council (2015) in contrast to the previous postures of the previous government. There are many other policy shifts that could be considered conducive to future cosmopolitanism, but all cannot be discussed within the scope of this section.

Cosmopolitan Electoral Change

The January presidential elections might prove to be a watershed in Sri Lankan political history in recent times. It is called a ‘silent revolution’ or a ‘democratic revolution.’ It was ‘silent’ because it eventuated through the ballot box unlike the Arab Spring. It was a ‘democratic revolution’ because it managed to oust the incumbent President who was authoritarian and at least undemocratic. He was contesting for an unprecedented third term, after changing the constitution to that effect through dubious means. If he managed to win the elections, the form of Sri Lankan politics would have taken a disastrous path.

At the presidential elections in January when he was defeated, Rajapaksa received only 47.6 per cent of the national vote, whereas his vote at the previous presidential elections in 2010 was 57.9 per cent. This was a 10 per cent swing in percentage terms within less than five years. In contrast, the common opposition candidate and the present President, Maithripala Sirisena, received 51.3 per cent for a comfortable victory whereas the previous opposition candidate in 2010, Sarath Fonseka, received only 40.1 per cent of the national vote. The increase was approximately 11.2 per cent.

More significant was the swing of votes at the parliamentary elections in August from the presidential elections in January. At the parliamentary elections, Rajapaksa contested again as a kind of unofficial prime ministerial candidate. However, his party, the United Peoples Freedom Front (UPFA), with considerable sections now opposing his politics, received only 42.3 per cent of the votes. This was a decrease of 5.3 per cent within seven months. The pre-January 2015 opposition and the interim government (UNFGG) between January and August 2015 received 45.7 per cent. This was also a decrease of 5.7 per cent, as two main constitutive parties of the common opposition in the presidential election, the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) (4.6 per cent) and the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) (4.8 per cent), as well as other smaller parties, contested the parliamentary elections separately. However, when taken together, it was an improvement of 3.8 per cent within seven months.

It is on record that Mahinda Rajapaksa attributed his defeat at the presidential elections to the Tamil vote and was hopeful of winning the parliamentary elections on the basis of the Sinhalese vote in the South. That was the case if only judged by the attendance at his public rallies. But that did not happen. As Nirupama Subramanian reported in The Indian Express (19th August 2015), after the last campaign meeting, Rajapaksa had predicted the following:

“In almost every district in southern Sri Lanka, I won the presidential election. Sirisena won only because he got the minority votes from Tamils in the North. But this is not a presidential election. This is different. We will win all those districts in this election again and get a majority.”

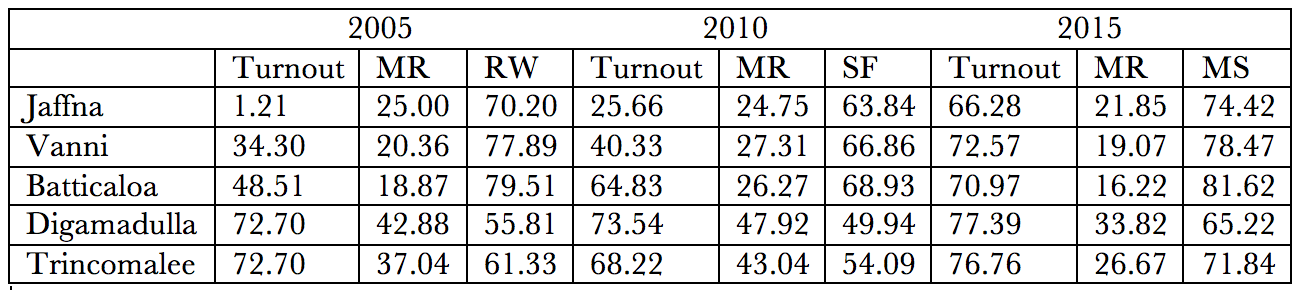

It is true that the Tamil vote particularly in the North and the East was decisive at the last presidential elections. They overwhelmingly voted for the moderate common candidate Maithripala Sirisena. It is interesting to note the voting behaviour of those Tamil voters as shown in Table 1 in the last three presidential elections: 2005, 2010 and 2015. The table gives percentages of votes in five Northern and Eastern districts for the seemingly moderate Sinhala candidates, Ranil Wickremesinghe, Sarath Fonseka, and Maithripala Sirisena respectively at the three elections. In all these elections, Rajapaksa contested. The candidates are denoted by their initials as MR (Rajapaksa), RW (Wickremesinghe), SF (Fonseka), and MS (Sirisena).

Table 1: Voter Behaviour at Presidential Elections in North and East (Districts)

Source: Department of Elections, Sri Lanka

As the above table shows those voters have preferred a moderate candidate (WR, SF or MS) at all three elections. That is what the percentages show for RW (2005), SF (2010) and MS (2015). At the last elections, MS won 74.42, 78.47, and 81.62 per cent of vote in the three districts of Jaffna, Vanni, and Batticaloa respectively. Even MR could not win such a percentage in his home turf, Hambantota in the South, even at the 2010 elections, which was 67.21 per cent in 2010 and 63.02 per cent at the last elections. The most important factor is the voter turnouts at these elections, in respect of voting for the moderate candidates.

At 2005 elections, there was extreme polarisation between the two communities or the North and the South. There was a pronounced boycott in the North (particularly in Jaffna and Vanni) engineered by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The overwhelming demand at that time was a ‘separate state’ and not ethnic accommodation. The voter turnout was extremely low: mere 1.21 per cent in Jaffna and 34.30 per cent in Vanni. It is true that the voters were prevented by coercion. However, even at the 2010 elections, the voter turnouts were 25.66 and 40.33 per cent in the respective two districts. What this voter behaviour shows is moderation, and an increasing ‘cosmopolitan’ disposition moving away from the extremism that was evident in 2005. Judging by these election results, there has been a clear desire and willingness on the part of the Northern Tamils in the country for ethnic accommodation at the last elections, both presidential and parliamentary, which have brought political change to the country.

Other Factors in Cosmopolitanism

The electoral behaviour of the other minorities, particularly the Muslims and the Hill Country Tamils, has been different. Judging by the positions of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) and the Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC), two main parties of the two communities respectively, what could be seen until lately is the willingness for political accommodation with the Sinhalese majority or the ruling party UPFA. Although both parties supported the moderate candidate, Wickremesinghe, at the 2005 presidential elections, both parties were willing to work with Rajapaksa after his victory in 2005, even at the risk of losing rank and file support. This was one reason for various splits and splinters from both parties. However, the situation was unviable particularly for the SLMC and the Muslim community by the time of the 2015 elections. There had been major attacks on religious places of the Muslim community since 2013. Similarly, there were attacks on evangelical Christian places of congregation during the same period. Therefore, apart from the Tamils concentrated in the Northern and some parts of the Eastern Province, the other dispersed sections of the Tamils (originally Northern or Hill country), the Muslims, and even the Christians were catalysts in bringing about electoral change both at the presidential and parliamentary elections.

There are other researchers who have employed regression analysis to examine voter behaviour between 2010 and 2015 presidential elections[31]. They have examined factors that contributed to the dramatic change in the ‘Mahinda Rajapaksa Margin’ (MRM) between the two elections and found that inter-district differences in the ‘share of all minorities’ played a key role, other than what we have discussed in Table 1 for the Northern and the Eastern districts. They have shown that the ‘share of all ethnic minorities’ combined with the ‘share of urban population’ in an electoral district/province have affected the MRM to drop.[32] Two other relevant variables, which the authors could have included in this regression analysis, are the ‘religious minorities’ (i.e. Christians) and the ‘share of youth’ in the electoral demography.

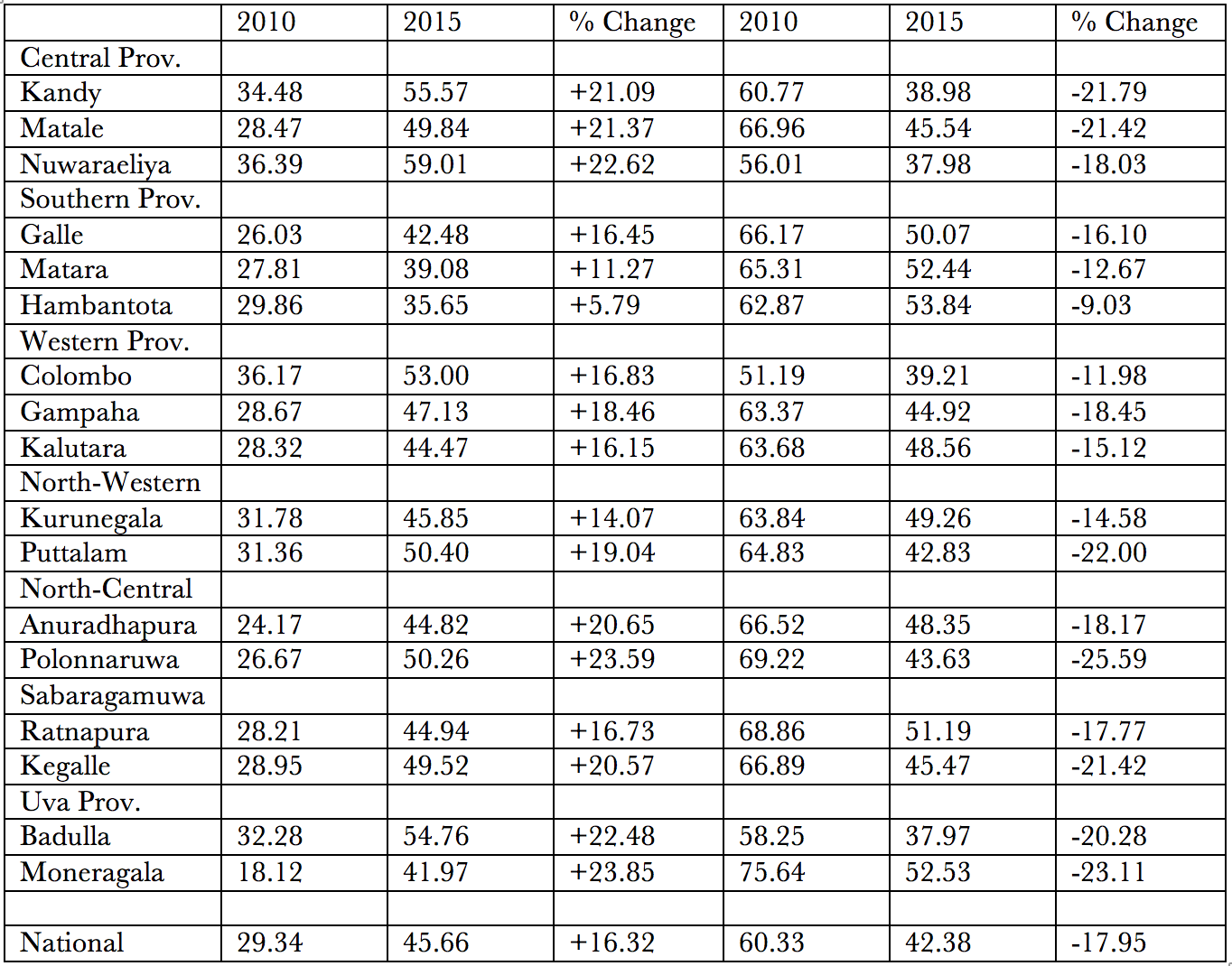

By the general elections in August, however, it became clear that even where the ‘share of all minorities’ has been absent or low, the MRM has dropped (i.e. Polonnaruwa or even Moneragala). This may be due to the ‘youth element’ or leadership factors. This is also where the cosmopolitan effect has emerged in the case of the Sinhala majority districts. It has been my conviction that urbanisation and modern youth play a major role in cosmopolitanism in any country and particularly in Sri Lanka. This is without a distinction as to ethnicity or religion. They are the people who are largely influenced by the ‘new news media’ discussed in Chouliaraki and Blaagaard (2014).[33] They are equipped with the ‘social media’ devices that Nalaka Gunawardene talked about in Sri Lanka this year.[34] Between 2010 and 2015, there has been nearly a million newly registered voters, all youth. The percentage of population and thus probably the percentage of voters between 18 years and 25 is nearly 15 per cent with a decisive say in an election. They may remain dormant without leadership particularly in rural areas. But when they are given leadership or opportunity they become activated. That is what was demonstrated in the August general elections. Table 2 shows the voter shift between the 2010 and 2015 parliamentary elections in respect of the two main contending parties/coalitions on a percentage basis in districts other than in the North and East. This is in a way the cosmopolitan shift.

Table 2: Voter Behaviour at Parliamentary Elections in Districts (Other than North and East)

UNP/UNFGG/UPFA

Source: Department of Elections and Wikipedia. Note that figures under ‘National’ include North and East.

As this table shows, the overall shift towards the UNP/UNFGG has been +23.85 per cent and the drop of MRM -23.11 per cent. The most significant shifts have taken place in districts where the ‘share of minorities’ or the ‘multicultural dimension’ is high. The Central Province, and its three districts – Nuwara Eliya (+22.62), Matale (+21.37) and Kandy (+21.09) – stand prominent. In this province, taken as an example, the share of the Muslims and the Hill Country Tamils stands high, but without a major shift among the Sinhalese, the above result could not have been possible.[35]

Another significant factor in the cosmopolitan shift in elections is the ‘share of urbanisation.’ The count of urbanisation in Sri Lanka is not very sophisticated. The urban population is still considered 18.4 per cent, counted on the basis of the population in municipal and urban council areas. Even if this methodology is acceptable, it has been an extremely slow and cumbersome process to upgrade divisional (rural) councils to urban councils or municipal councils. There are 23 municipal councils and 41 urban councils at present. If we take the municipal council areas as an example, all cannot be considered congruent with old electorates although names are the same.[36] For example, the Colombo Municipal Council area covers several electorates. However, it is interesting to note that out of 23 municipal council areas, the voting in 14 areas went significantly in favour of the UNFGG, and the UPFA could win only 6 areas at the last general elections in August. When it came to the urban council areas, the congruence between a parliamentary electorate and a local government area is complicated. However, most of the urban council areas out of 41 were located within the districts, which were won by the UNFGG.

Having said the above, the ‘cosmopolitanism’ of rural voters should not be underestimated. After all, Sri Lanka is a small country with high connectivity. As the above table shows, the highest drop of the MRM was in Polonnaruwa (-25.59) and then came Moneragala (-23.11), although the latter district could not be won by the UNFGG. What this shift signifies is the leadership factor, and at elections, the campaign factor countering parochial nationalism.

There were other cosmopolitan trends discernible at the parliamentary elections. For example, the extremist political parties could not get much of a foothold whether in the South or the North. The political party of the infamous Bodu Bala Sena (Buddhist Force Army), the Bodu Jana Peramuna (BJP), contested 16 districts but obtained only 20,377 votes, mere 0.18 per cent of the total polled. The fate of the Tamil National People’s Front (TNPF) was very much similar, obtaining only 18,644 votes in Jaffna and 0.17 per cent altogether. The UNFGG managed to win one seat each in Jaffna and Vanni districts showing also a trend of cosmopolitanism among the overwhelmingly Tamil voters, some of whom favouring national parties who assure minority rights.

Conclusion

There were two purposes to the present chapter, one theoretical and the other empirical or practical. The first part of the chapter outlined cosmopolitanism as a concept and a social philosophy, or one might even say an ideology, which could supply a viable alternative to narrow nationalism or ethnonationalism in the case of Sri Lanka or any other country. The second part of the chapter was based on the observation that cosmopolitanism is also a social phenomenon that might appear or disappear, like any other phenomenon, and that it has appeared at the last two elections in January and August in bringing desirable political change and democracy to the country. There have been emerging synergies between cosmopolitanism, democracy, and good governance. The empirical evidence related to the two elections were analysed to ascertain this cosmopolitan trend within the limits of this short chapter.

When cosmopolitanism is understood in that twin manner, it is an obvious conclusion to say that cosmopolitanism can be promoted both as a social philosophy or a public policy on the one hand, and as a political culture (with values and attitudes) through education with desirable social or electoral behaviour on the other hand. It is also evident that the social foundations of cosmopolitanism could be further expanded and strengthened through measures such as urbanisation, promotion of cultural integration of different communities, and technological advancements in communication. It is important to note that what appeared as an urban phenomenon with minority input at the presidential elections expanded into the rural areas at the general elections. Political leadership (i.e., President Sirisena, Prime Minister Wickremesinghe and former President Kumaratunga) and organisational factors (i.e., the UNFGG) in promoting cosmopolitanism might be the most decisive factors in this link at present and in the future. The modern youth equipped with information technology undoubtedly played (and would play) a decisive role in this transition both in the urban and rural areas.

*Many thanks to Prema-chandra Athukorala (Australian National University) for his clarifications on P. Athukorala & S. Jayasuriya, ‘Victory in War and Defeat in Peace: Politics and Economics of Post-Conflict Sri Lanka’ (2015) Asian Economic Papers 14(3): pp.22-54.

[1] J. Wickramaratne (2014) Towards Democratic Governance in Sri Lanka: A Constitutional Miscellany (Colombo: Institute for Constitutional Studies); A. Welikala (Ed.) (2015) Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects (Colombo: Centre for Policy Alternatives).

[2] K.M. De Silva (1986) Religion, Nationalism, and the State in Modern Sri Lanka (Florida: University of South Florida); A.J. Wilson (2000) Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism (London: Hurst).

[3] Much earlier analyses were by H. Wriggins (1960) Ceylon: Dilemmas of a New Nation (Princeton: Princeton University Press) on linguistic nationalism at the 1956 elections, and R.N. Kearney (1967) Communalism and Language in the Politics of Ceylon (Durham: Duke University Press) on communalism in general.

[4] Kearney (1967).

[5] N. DeVotta (2014) From Civil War to Soft Authoritarianism: Ethnonationalism and Democratic Regression in Sri Lanka (New York: Routledge).

[6] A. Bandarage (2009) The Separatist Conflict in Sri Lanka: Terrorism, Ethnicity, Political Economy (New York: Routledge).

[7][7] L. Fernando, ‘Sri Lanka’s Predicament: Ethno-Nationalism versus Civic-Nationalism’, Asian Tribune, 25th June 2007; L. Fernando, ‘Sri Lanka: On the Question of Nationalism’, Colombo Telegraph, 13th May 2013.

[8] L. Fernando, ‘A Victory for ‘Cosmopolitanism’ over Narrow Nationalism’, Sri Lanka Guardian, 29th August 2015.

[9] The pioneer advocate of jathika chinthanaya was Gunadasa Amarasekara, a popular fictionist. Later the main ideology became developed by Nalin de Silva (a professor) whose pioneer sketch of this ideology was in Mage Lokaya (My World) in 1986. See also, K. Senaratne, ‘Jathika Chinthanaya and the Executive Presidency’ in Welikala (2015): Ch.16.

[10] S. Vertovec & R. Cohen (Eds.) (2002) Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context, and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press); G. Delanty (2009) The Cosmopolitan Imagination: The Renewal of Critical Social Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press); D. Held (Ed.) (2010) Cosmopolitanism: Ideals, Realities & Deficits (Cambridge: Polity Press); G. Delanty (Ed.) (2012) Routledge Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies (New York: Routledge).

[11] G. Delanty, ‘Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism: The Paradox of Modernity’ in G. Delanty & K. Kumar (Eds.) (2006) The Sage Handbook of Nations and Nationalism (London: Sage).

[12]Although Rousseau criticised cosmopolitanism of Diogenes’ type, he was an advocate of ‘civic patriotism’ and not ‘ethnic patriotism.’

[13] P. Kleingeld (2012) Kant and Cosmopolitanism: The Philosophical Ideal of World Citizenship (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): p. 1.

[14] G. Evans (2008) Responsibility to Protect: Ending Mass Atrocity Crimes Once and for All (Washington: Brookings Institution Press).

[15] Kleingeld (2012).

[16] Ibid: 8.

[17] See J. Bohman & M. Lutz-Bachmann (Eds.) (1997) Perpetual Peace: Essays on Kant’s Cosmopolitan Ideal (Massachusetts: MIT Press).

[18] H. Kohn (1944) The Idea of Nationalism: The Study of Its Origins and Background (New York: The Macmillan Publishers); E.J. Hobsbawm (1990) Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

[19]Apart from Marx’s famous but often mistaken dictum that ‘workers have no nationality,’ his main thesis was arguing against Friedrich List’s narrow analysis of the ‘national system of political’ economy: G. Achcar (2013) Marxism, Orientalism, Cosmopolitanism (London: Saqi Books). Marx advocated a world outlook and analysis.

[20] E. Kedourie (1960) Nationalism (London: Hutchinson).

[21] Delanty (2012): p. 2.

[22] L. Trepanier & K. Habib (Eds.) (2011) Cosmopolitanism in the Age of Globalization: Citizens without States (Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky).

[23] Delanty (2012): pp. 38-46.

[24] U. Ziemer & S. Roberts (Eds.) (2013) Eastern European Diasporas, Migration and Cosmopolitanism (New York: Routledge): p.7.

[25] Delanty (2012): p. 3.

[26] Ibid.

[27] C.A. Chandraprema (2012) Gota’s War (Colombo: Ranjan Wijeratne Foundation).

[28] M. Christensen & A. Jansson (2015) Cosmopolitanism and the Media: Cartographies of Change (New York: Palgrave): p.5.

[29] L. Chouliaraki & B. Blaagaard (Eds.) (2014) Cosmopolitanism and the New News Media (New York: Routledge): Ch.8. It is interesting to note the emergence of a formative type of cosmopolitan solidarity in Sri Lanka during the Asian Tsunami in December 2004. Facing natural calamity, people, transcending ethnic and other barriers, got together. However, this trend did not last long. But the experiences seem to be absorbed by the youth.

[30] One important study in this direction is by N. Gunawardene, ‘Sri Lankan Parliamentary Election 2015: How Did Social Media Make A Difference?’, Groundviews, 3rd September 2015.

[31] Athukorala & Jayasuriya (2015).

[32] It may also be useful to undertake this analysis at the electorate level where the variations in these variables would be more conspicuous.

[33] Chouliaraki & Blaagaard (2014).

[34] Gunawardene (2015).

[35]This chapter does not attempt to analyse all the important figures in the table for want of space.

[36]The municipal council areas are: Colombo, Dehiwala-Mt. Lavinia, Kotte, Kaduwela, Moratuwa, Negombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Kandy, Matale, Dambulla, Nuwara Eliya, Badulla, Bandarawela, Galle, Matara, Hambantota, Ratnapura, Anuradhapura, Jaffna, Batticaloa, Kalmunai, and Akkairapattu.